|

Photo Credit: Fronteras Desk  What is your personal story and how do you connect it to your arts practice? I was born and raised in North Carolina. Although I was a child during the turbulent period of the 1960s, I witnessed a lot. I remember seeing signs over water fountains indicating “white only” or “colored only.” I remember black-only movie theaters and swimming pools because we weren’t allowed to go to the white swimming pool or white theaters. My father’s mother lived in Wilmington, NC. As a kid we’d travel to visit her from my home in Raleigh several times a year. Because we traveled through the heart of Klan country my parents would have me pee into an empty soft drink bottle, afraid of stopping at white-owned gas stations. Yet, in the midst of this craziness, I went to an alternative Quaker boarding school when I was 12, where I was one of 3 black kids out of a student body of 24. I was in this culturally rich, integrated, loving environment for 3 years which were the formative years of my life from ages 12–15. My first experience in a darkroom occurred at the Quaker school. My exposure to a life of service and living simply with consistency between one’s politics, spiritual practice and one’s work happened at the Quaker school. Ironically, the examples of the worst of humanity and the best of humanity were found in the same state. Both the experiences of hardcore racism and loving pacifism with a strong sense of community influence the work I do now and my art practice, which I identify as a celebration of the dispossessed. What themes are present in your art? I come from a tradition of humanistic, documentary photography. Traditionally, this photography is black and white and focuses on the process of getting to know people over an extended period of time and attempting to tell their story and reveal their truths through photo essays. I just did a retrospective show in December and the themes were primarily those of love, compassion and empathy –moments from everyday life that have a universal quality. Can you tell us about the medium in which you create? I spent 22 years shooting black and white film, which I developed in my home darkroom. Though this resulted in several gallery shows, the people I photographed weren’t seeing the work. I’ve always been drawn to street art since it first blew up in the early 80s. I spent 3 months in Brazil in 2009. During this period I spent time with artists creating art on the street. The artists in Brazil showed me work by the French artist JR, who enlarges black-and-white photographs to cover the facades of four-story buildings. This was my first time seeing how a photograph could be used as a street art medium. Upon returning to the Navajo Nation, I began to experiment with my old negatives and started placing them along the roadside on the reservation. I learned early on from roadside vendors that they appreciate having art on their roadside stands as it encourages more tourists to stop. Also, in a community with a high rate of unemployment, high rates of teen suicide and drug and alcohol abuse, I wanted to use imagery along the roadside that reflected back to the community some of the values of love and cultural heritage I’d captured during my time on the Navajo nation. Since 2009 I’ve been using large-format, wheat-pasted, black-and-white photographs adhered to roadside structures as my primary medium. What is JustSeeds and why are collectives important? Justseeds is a cooperative of 30 socially-engaged artists and activists scattered across north America whose work addresses themes of social justice, environmental justice, gender quality, prison reform, veteran advocacy and so on. It was an honor for me a year ago to get invited to join this group of like-minded folks advocating for the collective good. To live and work in relative obscurity on the Navajo Nation, it's important to feel connected to a larger community where ideas are shared and critically evaluated. I also appreciate opportunities for collaborating. You asked why are collectives important. A book of activist art was published recently titled "When We Fight, We Win." I'd alter that by saying when we fight together, we win. Do you think that Arizona has a unique aesthetic voice? No doubt. There are the cliché images of Arizona art of coyotes wearing bandanas howling at the moon or Kokopelli, but then there's the more socially-engaged art that speaks to immigration issues such as SB 1070, illegal deportation, protection of sites sacred to local indigenous tribes, water use and coal and uranium mining. Arizona is in a unique position to serve as a model for the remainder of the country with legislation regarding protection of sacred sites, immigration reform and gun law reform after the tragic shooting Tucson in 2011; however, politics and mindsets being what they are here, it provides an ongoing opportunity for activist artists to keep fighting to shed light and spread love. As Martin Luther King, Jr. said, "the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends towards justice."

0 Comments

Can you share your personal story and how it connects to your art practice? I grew up on the US/Mexico border and have lived on both sides of the fence: in Douglas, Arizona and Agua Prieta, Sonora. My family and I have lived primarily in Douglas. We lived in Agua Prieta during my middle school years and I always remember how often we would cross back and forth, sometimes 2 to 3 times a day. We were "regulars" at the port, my mom’s name and car were known by the majority of the custom agents, and we definitely had our favorite agents whom we hoped would "check" us. Rather than the questioning being about why we were crossing or what we were bringing back, the interaction was more about how our weekend was, or how the agent’s parents were doing and vice versa. At the age of twelve the experience of living the border daily was not only mundane and routine, but it involved friendly interactions and relationships with federal agents. For my brother and me, it was a game of whose turn it was to pick the lane and guess which agents would be waiting for us. Fast-forward to 2005, which is the year I moved to Phoenix to pursue a degree and career in art: I found out quickly that my experience of the border was incredibly different from the perception of the people around me. My art practice became rooted in my quest not only to change that often negative perception, but to expose it. What are the themes of your artwork, and why do you choose them? The themes of my work range from feminist perspectives, life as a border citizen and, at times, a combination of the two. These themes chose me because they define me as a female who has grown up atop a geopolitical boundary too often used as political fodder and not regarded enough for its fertile, rich and vibrant culture, people and scenery. As an artist, I can have a voice in the public sphere that makes visual what the border means to me. What I love about making art about the border is that it's not only about Douglas and Agua Prieta, but it can mean something to folks living on another border somewhere else in the world. I hope the meaning can transcend geography, cultures and ideologies. Do you think there is a unique aesthetic and artistic movement in Arizona? Yes, I think there is a movement in Arizona. To me, the movement is about the simple fact that we're all the same, fence or no fence. Whether you are from that side or this side, it shouldn't matter, and it shouldn't give us the right to act unjustly to one another. The aesthetic movement has recently been about the border fence, which speaks volumes for a community like Douglas, as we're in the process of redefining who we are as a city and globally-relevant place. If you consider the recent work of Postcommodity, Ana Teresa Fernandez, Gretchen Baer and Aspir JHF, all of them used the physical fence as material to create art. The themes of these works are about remembering and imagining a time when the fence was non-existent, and the way in which we are connected not only through blood, but also through symbols and systems like capitalism. Artists want the world to know we are the same on both sides of the fence. In many cases we are literally family, and many people are disregarding history and where they came from at a time when we are bombarded by negative rhetoric surrounding our community. I feel artists are stepping up to represent this sentiment, which not only holds regard for the battles we're as facing as a border community, but also the battle that indigenous people and minorities are facing in the U.S. and abroad. What projects are you working on now? What can we expect to see from you in 2016? The Mexican Woman's Post Apocalyptic Survival Guide in the Southwest: Food, Clothing, Shelter, y La Migra is the newest project I am working on, which is a multiphase piece that consists of large-format photographs of 12 women who live in Agua Prieta, Sonora, and who are part of the non-profit organization DouglaPrieta. These women are experts on living sustainable lifestyles: they run a communal garden, raise livestock, make clothing, produce bricks for building --all while living on the outskirts of a highly-militarized border. The second phase of the project will be a how-to book co-produced by the participating women. This project is supported in part by an Artist Research and Development Grant from the Arizona Commission on the Arts. How do you feel that art can create or support social change? Art supports social change. Actually, it creates social change. That's something I think many artists imagine. That's what keeps us doing what we do. At the end of the day, if our art sparks an out-of-the-norm conversation or inspires a new perspective, I think that's great in and of itself. In my opinion, as artists in this technological generation that is hyper-connected, so many of us feel responsible to change the world. I believe in the power of numbers and consistency: if you have a message, find 100 ways to say it, and then invite someone else to say it with you. Can you share your personal story and how it connects to your art practice? It’s hard for me to separate my personal story from my arts practice. Growing up in rural Arizona near the US-Mexico border, art was first a tool for escape, a tool for imagining an experience larger than my immediate surroundings. What I didn’t fully appreciate at the time was how much that landscape would continue to manifest itself in my work: the huge sky, the rolling grasslands, the continual thirst for rain. Also the linguistic and cultural landscapes, the physical reality of the border as a dividing line, the edge of the world–– that’s how it was first presented to me. Later, after living for most of my 20’s in central Mexico, I came to understand my experience as that of a fronterizo–– though my blood is Irish-Slavic, my cultural experience is inseparable from the border. My poems are written in Spanglish because that is my most comfortable linguistic mode. To be bilingual is to be a bridge. To have privilege is to have the responsibility to spread it and subvert it. An awareness and engagement with social justice is a necessity. I’m always moving between worlds and arts media. What are the themes of your artwork, and why do you choose them? I find that others are better at articulating themes in my work than I am. That said, for me it’s the land. And how cultures interact with it. I am of a place that is staggeringly beautiful, and laced with deep injustice. Do you think there is a unique aesthetic and artistic movement in Arizona? Claro, though it’s hard to put my finger on it. I know that the last five years have been especially tough here: SB1070, Ethnic Studies ban, austerity, abysmal education funding, increased militarization, public officials running on fear. Thing is, it’s a lot bigger than the last few years, all this stuff has roots that go way way back–– at least to statehood, to colonialization and indigenous genocide. All that said, to associate the word Arizona only with backward politics is just lazy. Look beyond the headlines, spend time here, attend events, break bread with community. What’s beautiful is the way artists and communities have responded to the oppression, both directly and indirectly. The arts movement is Arizona is socially engaged and community-based because here there is no other way. There’s something about how the artists work together here, something about the land too. The desert is simultaneously a muse and a killer.  What projects are you working on now? What can we expect to see from you in 2016? My practice took a big turn in 2015 after the publication of Sonoran Strange. I unexpectedly had the opportunity to buy a house in Tucson, and for the first time I have a small piece of land for which I am responsible. Lately I’ve been spending my time swinging the pick and shoveling earth, quite literally doing groundwork. I’m building a rain-fed urban desert oasis that will partly feed my family and community. I’m interested in the intersections of permaculture, venue design, community, performance and relationship to place. Only recently have I begun to realize that this work isn’t taking away from my ‘art time,’ rather this is my art in this time. This is also arts practice. I hope to apply what I learn on this project to other, larger and more public spaces. Which leads me to think about La Pilita, the small venue in Tucson’s Barrio Viejo that I’m now co-managing with the social justice & spoken word organization Spoken Futures. Art has such a beautiful way to bring people together, in 2016 we’re looking to begin using this small space to affect long-term impacts on Tucson’s cultural landscape. Adam Cooper-Terán and I continue to collaborate as Verbo•bala Spoken Video, and this year we’re scheduled to work with Borderlands Theater and others to create a new series of performance vignettes in the style of the Sonoran Strange performance. We’re going to be looking at specific sites in the Tucson basin that are tied to local identity and culture. I’ll also continue working with young people at a local alternative school, with Spoken Futures, and while traveling. I’ve been working professionally as a DJ for many years now, and this year I’ll continue to play 1-2 days a week, Friday nights at Hotel Congress and beyond. Hopefully amongst all of that will be the time when poems come. In what ways does performance impact social change? In other words: Why performance? My colleagues Faviana Rodriguez and Jeff Chang of CultureStrike are fond of saying that you change the culture first, then the politics will follow. I can’t think of a more succinct way to put it. If we’re going to survive as a species and maintain our humanity, we’re going to need to stretch our imaginations in new directions and depths. Performance for me is the laboratory, a space of free imagination, where the body opens its vocabulary and arts media mix–– in performance we expand what’s possible, what stories are told, how, and by whom. Performances weave themselves into the consciousness of an audience, and from there to wider society. And that’s just the beginning of what performance does. You can find more information about Logan Phillips' work: www.sonoranstrange.com |

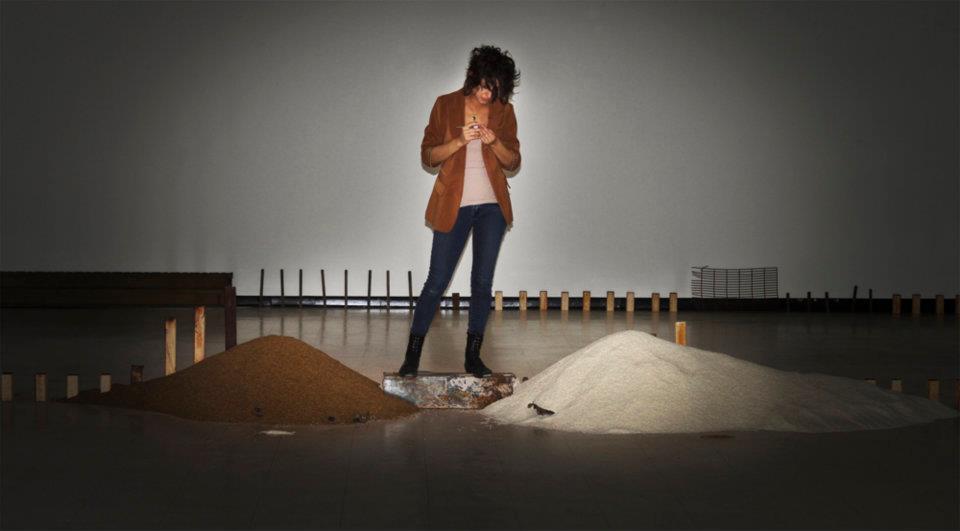

Banner photo by:

Carlos Antonio

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed