|

Photo credit: David Emitt Adams

Can you share your personal story and how it connects to your art practice?

I’ve lived most of my life on a divided line, living in a linear world with a nonlinear mind. I’ve always wanted to communicate using my own personal format. This has lead to a lifetime of developing that format and is always a work in progress. The need to touch and build with my hands has always been a part of my life and, with that, I feel very privileged. Often, my family moved to new towns and cities. This was an accepted part of my life that helped me keep a fresh perspective. I believe this, and my Indigenous roots, have been a major contribution to my art practice. What are the themes of your artwork, and why do you choose them? As a contemporary artist who practices largely in Indigenous issues, I often trace my concepts through the western projected narrative as well as a rooted personal Indigenous dialog. Historic western imagery and ideals act as stains that hammer through most of my work and position themselves into boldly-laced discussions. Imprinting an expired label onto archaic capitalistic driven social constructs tends to be my main target. I continually find a need to make a call for Indigenous-minded social, political, and environmental progression within our society. The lack of it has buried us and left us with a disconnected reasoning with ourselves.

What does it mean to you to be an artist living and working in Arizona today?

Arizona is a wonderful place. It is Indigenous land that still responds to the people that belong to it. It also has a bit of a bite to it that stirs the dust and strikes discomfort into the eye of humanity. These are the things that keep me, as an artist, alive and attentive. I appreciate what it has given me and I’m always working diligently to give it justice. What projects are you working on now? What can we expect to see from you in 2016? I’ve been pretty busy at the turn of the year moving my print shop, WarBird Press, into a more public space. With this accomplished, one project that I’ve been fixated on has been my letterpress work that I’m using for public engagement. I have an old vending machine that was used on the streets to sell newspapers and I’ve been exploring the levels of public interaction with it. The history of prints, prints as media and as propaganda, are deep within the documentation of our internal framework as a society. I’m revisiting that narrative by applying adjusted prints to the existing archives. Random and some not-so-random places in the public are scouted as drop spots for the vending machine. The prints are then placed inside for the public to purchase at a price well below market value. Newspaper vending machines have quickly been driven to the shadows of society by digital media and, with that, the main use of the print as a multiple has been lost. I use digital media as the conductor that directs traffic to the specific location of its predecessor. It’s a play to recall our conditioned notions that frame the selected notes of history.

2 Comments

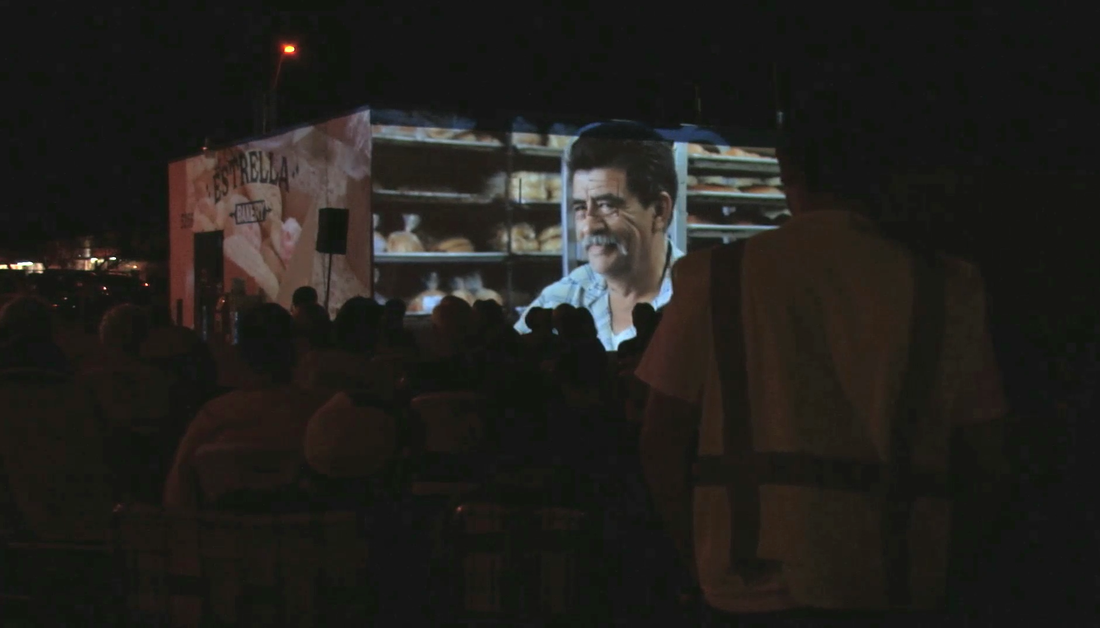

Through original videography, community events, street art and urban site-specific projections, Barrio Dulce celebrates pan dulce and the Mexican bakeries that support neighborhoods, community and culture. Pan dulce is hand-crafted artisanal bread made by proud bakers, and consumed daily by many people in the Tucson, Arizona and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua where the Barrio Dulce project has been produced and presented. During the project, artists Gabriela Duran and Heather Gray worked with La Estrella Bakery (http://laestrellabakeryincaz.com/) in Tucson and Panadería Aurora in Juárez and recorded interviews and video of the baking process, gathering stories from the owners and workers, gathering stories from the owners and workers. Barrio Dulce hosted screening events at the bakeries or nearby, rather than screening the videos to an outside audience at a theater or film festival. At the events, the videos are remixed and projected large-scale on the buildings. The images and sounds light up the neighborhoods, and the bakeries publically perform their stories, which are normally hidden behind walls. Neighbors gather in the streets or parking lots, eating pan dulce, and watching the projections animate a space they might visit everyday.

How does this project exist bi-nationally? Tucson and Juarez are cities with strong traditions of pan dulce. They are of similar size and latitude with distinct “border identities”, and social and political issues that are tied to border dynamics. The project has also been presented live in Guadalajara, and exhibited in Valparaiso, Chile --cities with their own incredible traditions of bread and baking. The project was created by Gabriela Durán, a new media artist and professor at the Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez, in collaboration with Tucson-based artist and videographer Heather Gray. Gabriela is connected directly and emotionally to the project because of memories of growing up in her father’s bakery in her neighborhood in Juárez. About halfway through the project Jellyfish Colectivo (http://jellyfishcolectivo.com), a street art collective in Juárez, joined us and created a mural celebrating negocios del barrio leaving a more permanent mark in the neighborhoods. What does it mean to be artists living and working in Arizona today? It is an enormous privilege and responsibility to live in a desert and a border region. A lifetime of questioning and learning is required to try to understand how to live in a place that is both fragile and resilient with a complex history of migration, and colonization. Heather has lived in Arizona her whole life. Gabriela has lived in Juárez her whole life. They are committed to staying, inspired by the way artists and communities respond to the political climate, assert themselves and their stories, survive, and seek justice and social change.

What can we expect to see from Barrio Dulce in 2016?

We are focusing on bringing Jellyfish Colectivo for their first street art engagement in Tucson, to continue the cross-border exchange and conversation. There is still a lot of information we have the needs to be presented. For example, when we were doing interviews in Juárez, we learned that bakers used to have a union that helped create fair paid jobs for bakers. We also found unique stories about each bakery. For instance, there was one bakery in Juárez that, in its golden years, would be open 24 hours. People would go at 4am to get a sweet bread and free coffee. We would like to present this part of the project either online at barriodulce.com or at a conference. How do you feel that Barrio Dulce creates or supports social change? Today, many Mexican bakeries and other small businesses on both sides of the border are disappearing, downsizing or automating their process under pressure from supermarkets, low-wage jobs, downturned economies, urban revitalization schemes, marginalization of migrants and violence. As a result, decades of memories, skills, meaningful well-paid jobs, and culture with connections to place are at risk. The two cities face different threats, though it is the same source --the globalization of corporate neoliberalism-- which has different consequences on each side of the border. Barrio Dulce poses the idea that something as humble as a bakery holds a margin against these threats. The projections at the bakeries help rethink a relationship to the city and neighborhood itself. Our project reflects upon the importance of Mexican bakeries, not only in terms of community but also seeing how they form and affect our identities, activate the local economy, and create safer environments. Without overstating the impact of one art project, we see the need for creative responses to our situation, because we know art has the power to shape the collective imagination over time. DulceTucson from Heather Gray on Vimeo. |

Banner photo by:

Carlos Antonio

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed