|

Please share a little of your story/background and the way your personal story connects to your artistic practice(s)? I’m a fronteriza or borderlander woman as well as a first generation Mexican American of dual citizenship. It took me time and lots of research to come to fronteriza as a primary word to identify myself. Growing up on the border of El Paso, TX and Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua was unique and conflicting because I rarely, if ever, saw my community represented in mainstream media, at least not in a positive way. In hindsight, I believe that one of the reasons why I shared a common disregard with my young peers about “home” was because we didn’t fit into the “all American” or Mexican narratives, so El Paso/Juarez felt irrelevant among the two national identities. The fact that neither Mexican American nor Border History was (and still not) part of public school curriculum in El Paso was also unfortunate to our knowledge of self and pride in our community. I was only motivated to learn about border history once I moved away from home and was constantly confronted with the question, “Where are you from?” The search for my history and identity became a personal, political and creative quest to define myself and anchor my voice as an artist representing U.S./Mexico border life and culture. What themes or topics do you address in your artistic and cultural work? Using my family’s personal oral histories as the foundation for my El Paso/Juarez border research, I have found several topics especially relevant including, immigration policy; labor demands and trade agreements between the U.S. and Mexico; the War on Drugs and its effects on border people; femicide and the role of women as workers, organizers and leaders of their families and communities. My family’s stories allow me to personalize these themes as tangible and life altering experiences that have directly affected my grandparents, parents, siblings, extended relatives, and ultimately myself. Sharing these stories through theater gives me access to the creative and emotionally rich range of performing my family’s personalities and border culture in an intimate way. The goal of my artistic work as it pertains to border identity is to humanize and honor our unique experiences as fronterizos who are often overlooked in American history and politics. Why is artistic expression important to political and social justice movements? I believe that artistic expression is at the core of human existence. We use our bodies to create songs, stories, dances, images, words, plays and many other works in an attempt to express the truest sentiment of who we are and what we’re going through. It is inevitable then that art would serve as a means to express how we feel about the injustices we experience to relieve our grievances and address the issue(s) at hand. Historically art has connected us as people and as a common voice towards creating cultural and political change. For me it is a positive reminder that we are the makers of culture and politics. This is why representation matters; because seeing ourselves through the arts inherently empowers our agency as creators of the society and world we want to live in. What is unique to Arizona aesthetics? Do you see a special arts movements happening here, if so, what does that look and feel like? In other words, why should people be paying attention to Arizona artists? I’m not from Arizona but I feel connected to it through our shared natural desert landscape, political history and heritage as the southwest region of the United States. The southwest is historically contested land where U.S. imperialism is continuously reinforced through laws that reflect a bigoted sense of white American patriotism. On any given day we can watch news of anti-immigrant policies and Trump’s proposal to build another US/Mexico border. Unless one lives in the southwest, one may never know the effects of border enforcement and militarization on local communities. Now more than ever Arizona artists are invaluable voices of local concerns who can disseminate information in creative and relatable ways that raise awareness, connect and motivate national and international action against today’s racist and xenophobic policies. I’m grateful and inspired to be part of the Bi-National Arts Residency this year, building towards cross-border artistic collaboration with Mexican residents living across the border from Arizona. What is on the horizon for you, and what would you most like to learn this next cycle in your practice? I want to continue working to be the best storyteller I can possibly be through performance and writing. I’ve always been interested in exploring film and TV and I think it’s time to pursue it. For more information on Yadira De La Riva's work: www.yadiradelariva.com

And for for more information on the ASU Performance in the Borderlands residency: http://tinyurl.com/ASUPIB Yadira's public show of "One Journey" will be in Phoenix on Weds. October 19, 7 pm (Rio Salado Project 2801 S. 7th Ave. Phoenix, AZ)

1 Comment

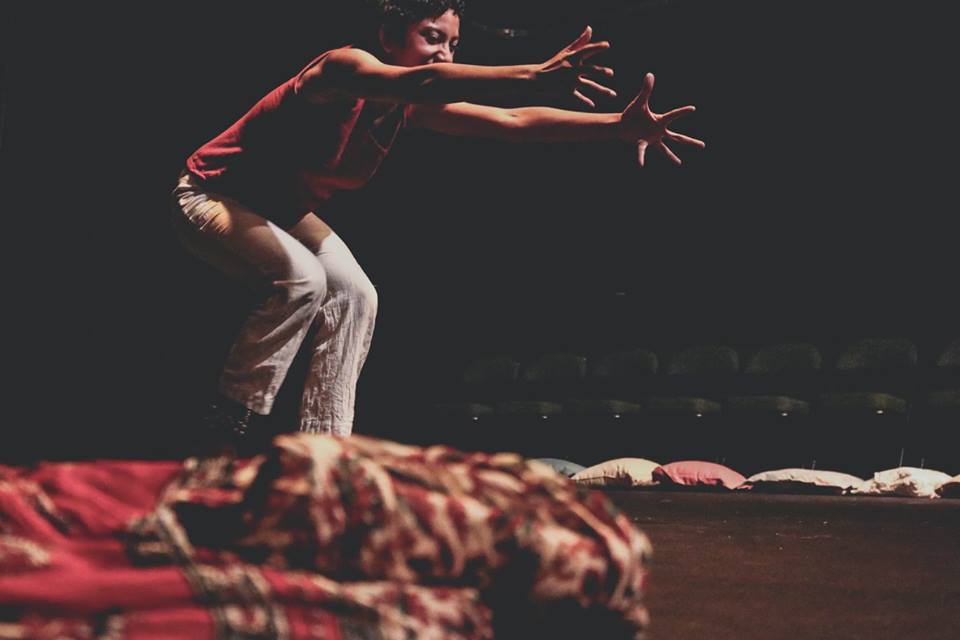

¿Podrías compartirnos un poco de tu historia personal y hablar de la forma en que ésta se conecta a tu práctica artística? Creo que desde muy pequeña desarrollé esa sensibilidad que permite observar o crear desde diferentes ángulos de interpretación. Claro, ahora a mis 30, puedo ver con otros ojos esa experiencia. Durante mi infancia fui muy introvertida. En lo personal, no tuve una formación artística ni en mi entorno familiar, ni en la escuela Al terminar la preparatoria, atravesaba por una circunstancia familiar que me llevó por un camino de búsqueda personal. Tomé un empleo temporal en una cafetería cerca de casa, frente a la Universidad (UABC). Ahí mismo me inscribí en un taller de fotografía con el maestro Manuel Bojórkez y compré mi primera cámara análoga en un bazar de la calle cuarta, en el Centro. Quizá esa fue una pauta (consciente o no) para llegar a donde me encuentro hoy. Me maravilló el lenguaje fotográfico; el sólo hecho de crear imágenes a partir de luz y tiempo. Podía pasar horas en el cuarto oscuro, manipulando las formas, la textura del grano, de la sal. Ya en la Universidad, continué con mi formación fotográfica en el taller de Julio Blanco y presenté un trabajo sobre la indigencia en Tijuana (problemática social que ha crecido en los últimos años). Recuerdo que en uno de los recorridos en busca de personajes que quisieran compartir un poco de su historia de vida, me acompañó Saulo Cisneros, un artista de Tijuana. Al final, en la exposición de este taller sucedieron dos cosas maravillosas: Octavio Hernández, promotor musical y director de la revista TijuaNeo (q.e.p.d.) me invitó a publicar una selección de mi trabajo; y conocí a Hanna Silbermayr, una fotoperiodista de Viena que investiga sobre migración y desigualdad global, y a quien acompañamos en un recorrido por la canalización del río Tijuana, hogar de muchos indigentes e inmigrantes hasta el día de hoy. ¿Cuáles temas o asuntos tocas en tu trabajo cultural y artístico, y por qué? Qué medios prefieres usar en tu trabajo? En este camino hacia la autonomía creativa, me han interesado diferentes temas y he ido explorando en las estéticas que reconfiguran esa subjetividad: desde el surrealismo, el materialismo, la migración, la protesta social. Actualmente me interesa dialogar en torno al cuerpo como un ente constructor de identidad personal, colectiva y su relación con el contexto político, pero también como un espacio metafísico donde de formas a veces indecibles, la existencia cobra sentido. El cuerpo en movimiento a través de la danza, pero también la meditación; por ende, una relación entre cuerpo, mente y espíritu. Los soportes para navegar estas corrientes creativas han ido desde la fotografía, el cine documental, la danza, y la poesía, siempre la poesía como ese germen que está creando y generando nuevos microorganismos. ¿Por qué la expresión artística es importante en los movimientos de justicia social? Justo ahora recuerdo a Luis Camnitzer, un artista, poeta y teórico uruguayo al que tuve oportunidad de escuchar hace unos meses en Tijuana, durante el último Congreso de la Facultad de Artes de UABC. Realizó una crítica al mercado del arte y a las lógicas imperantes del capitalismo como métodos de manipulación; habló de su visión de la pedagogía freireana y la consciencia política; del arte como el pasaporte imprescindible para la salud mental. Pienso en el arte como la voz de los pueblos a través del tiempo, de la historia, de las épocas. Lo que da vida, lo que libera. Esa conjunción entre decir y ser, entre pensar y hacer. Atravesar los límites del lenguaje, de la mente, del territorio. Salir de la prohibición estructural y contar la historia que nos compete, pero no callar. El arte como esa luz que no se apaga, como flores para no olvidar. Hace poco, durante un taller en Tijuana, me sorprendía un poco de la reacción de mis compañeros al hablar de la danza ritual y la relación del cuerpo con lo político. Percibí esa tendencia colectiva de asumir lo político como aquello que sólo sucede en las esferas arcaicas del poder y la corrupción, y no como un entramado de subjetividades que aludan a la pluralidad. ¿Puedes compartir un poco sobre tu proyecto actual? Sensorama se ha ido tejiendo de muchas fibras áureas. Inicia como un proceso de escritura autobiográfica, hace ya casi cuatro años. La poética gira en torno al ritual personal de sanación a partir de dos experiencias personales: la enfermedad del cuerpo, la nueva sangre, y la muerte de mi padre. Además, en relación al contexto social y político, ha significado una suerte de alteridad necesaria para asimilar el duro golpe de la violencia y la negación de nuestros cuerpos: sean desapariciones, violaciones, feminicidios. Ha sido causal también la experimentación con otros lenguajes, como la integración poética de la música, el cine. Desde hace un par de años pensaba en un guión para cine a partir de la poética del libro; se trataba de una danza ritual con mis amigos y amigas más cercanos en Tijuana: la tribu; que además tengo la fortuna de aprender de sus propios procesos ya que son artistas visuales, bailarinas, músicos. Tuvimos una que otra reunión pero se fue quedando atrás por la circunstancia de cada uno: fuera trabajo, presupuestos –en mi caso, como productora-, etc. Realicé una primera experimentación audiovisual con mi amigo Checo y quedó chido, pero seguía con la documentación y el trabajo creativo, con el ritmo natural de la vida. Con Sensorama busco recuperar el carácter ancestral de la danza, pero también integro la ritualidad y performatividad de la danza butoh y la danza del vientre estilo tribal; ambas tienen una relación política, si se analiza su origen y su contexto. La primera, por ejemplo, la entiendo como reconfigurar el cuerpo con la mente y el espíritu a partir de un contexto de violencia, de guerra. Esos son los actos que considero verdaderamente revolucionarios, elevar el espíritu creador aun en tiempos de penumbra. Además de esas experiencias concretas de compartir procesos creativos, hubo muchas lecturas de investigación; conversaciones largas con mi compa Checo –artista visual del Norte-, relecturas, revisiones, correcciones; todo este proceso de escritura aunado a mi practica física-corporal. Me interesa absolutamente el autodidactismo y la transdisciplina, y Sensorama me ha brindado la oportunidad de ritualizar y colectivizar el trabajo estético. Por ahora me encuentro haciendo unas pequeñas adaptaciones para presentar la pieza escénica en el Festival de Literatura del Noroeste en Cecut, Tijuana, el próximo mes de noviembre; me encantaría que podamos volar toda la parvada, el maravilloso equipo formado hasta hoy. Además, trabajando en la parte operativa y de gestión. Tengo confianza en que el proyecto seguirá creciendo, como ese jardín poliforme del que hablaba antes. ¿Qué viene en el futuro para ti, artísticamente? ¿Qué es lo que más te gustaría aprender en este nuevo ciclo de tu práctica?

Deseo seguir aprendiendo en cada una de las áreas en donde he transitado. Además de seguir trabajando en Sensorama, y poder viajar a otras latitudes para nutrir mi formación escénica, tengo en mente la escritura de un guión para cine; una narrativa basada en un viaje por carretera que hicimos el año pasado dos amigas y yo: Carretera Salvaje. También, ahora que deambulo por este centro, he estado componiendo canciones junto a Las Hermanas Bastardas. Echándole fuego a la hoguera. Con las hermanas vienen procesos bien chingones, ya que sigo aprendiendo en base a la armonía, el ritmo, el pulso, la ecualización y esos bellos aconteceres musicales. Estoy por echar a andar un proyecto en el que he puesto el pensamiento durante un largo tiempo, y lo asumo como una manera lúdica de unificar y concretar mi ser pedagógico con mi ser poético. Crear comunidad a partir de procesos creativos. Además recién me he unido a la organización de una Caravana poética que recorrerá el país entre diciembre y marzo próximos, junto a Las Hermanas Bastardas y creadores que se vayan uniendo al proyecto. No sé aun cómo lograré equilibrar todo esto con la escritura de mi proyecto de titulación de la licenciatura, pero es algo que tengo en mi lista de prioridades. Esto porque aun cuando he decidido dedicarme enteramente al arte y la poesía, la investigación y la teoría me cierran el ojo coquetamente, y quiero seguir caminando y atravesando todos los engranajes que unen tanto mi locura como mi sentido a este mundo. ASU's Performance in the Borderlands to Showcase "Voices of Power" in Metro Phoenix

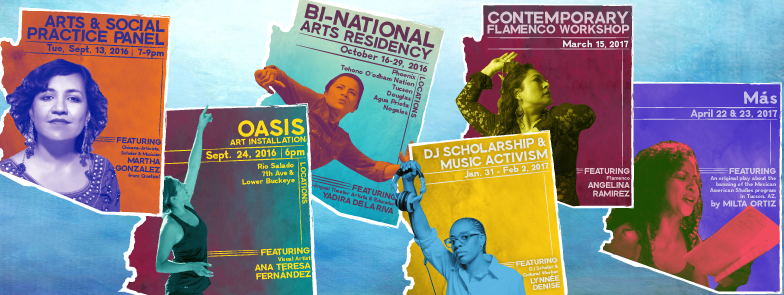

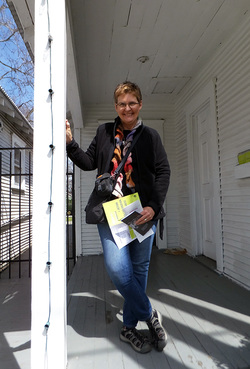

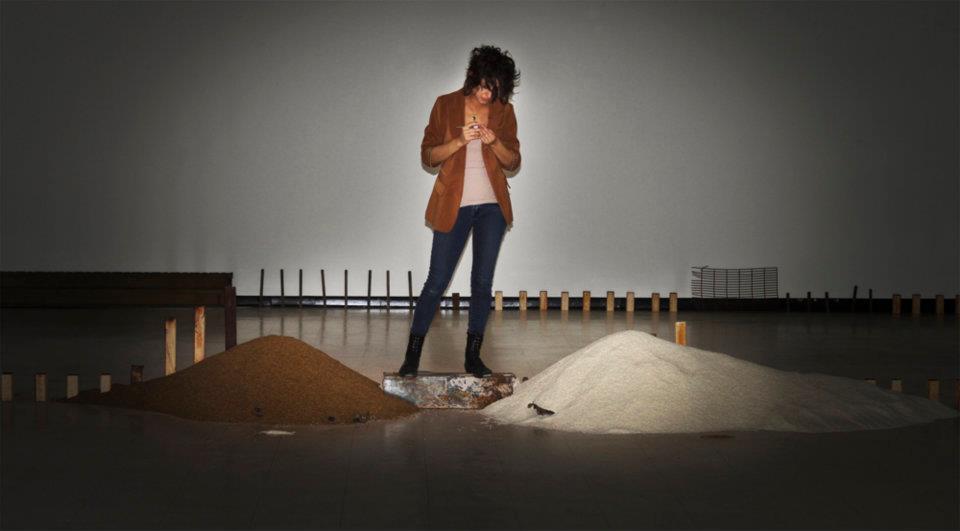

TUESDAY, AUGUST 30, 2016 AT 6 A.M. BY LYNN TRIMBLE Phoenix New Times http://www.phoenixnewtimes.com/arts/asus-performance-in-the-borderlands-to-showcase-voices-of-power-in-metro-phoenix-8581450 Performance in the Borderlands, an Arizona State University initiative addressing the intersection of arts and culture with border-related issues, recently announced its 2016-17 season. The season includes a robust lineup of artists working in visual art, theater, dance, and music. Its theme, “Voices of Power,” reflects a focus on women of color in the arts, and their role in affecting social justice within and beyond border communities. Mary Stephens, producing director for Performance in the Borderlands, describes this season as her favorite to date. “This is a dynamic season that brings artists and cultural workers from both sides of the border together to change the politics and perceptions of the Sonoran Desert,” Stephens says. EXPAND Performance artist Yadira De La Riva. ASU Performance in the BorderlandsPerformance in the Borderlands launched during the 2003-04 season, and has engaged artists from Mexico, Argentina, California, and Arizona in exploring such issues as immigration, LGBTQ rights, and the Black Lives Matter movement. This season kicks off with a collaboration with ASU Gammage Beyond Resident Artist and Grammy Award-winner Martha Gonzales, whose public conversation and music demonstration at Phoenix Center for the Arts happens on September 13. The event includes a panel discussion with Liz Lerman, Jaclyn Roessel, Marlon Bailey, and Monica de la Torre. After that is Oasis, comprising an art installation and performances by Ana Teresa Fernandez, whose previous work includes symbolically erasing the U.S.-Mexico border by painting a portion of border fence to match the blue sky above it. Her site-specific installation at the Rio Salado Project on September 24 and 25 addresses land displacement, immigration, and water usage in the desert. It includes performances by several Arizona artists, including Raji Ganesan, Leah Marche, and Liliana Gomez. Visual artist Ana Teresa Fernàndez. Deanna Dent/ASU Now“We hope the season helps people recognize the contribution of women of color in the arts and brings a deeper awareness of the politics of place,” Stephens says. “This year we’re really interested in showcasing the work of women as political activists and visionaries.” October offerings include a bi-national artist residency by Yadira De La Riva focused on theater as a tool for social engagement. In November, Performance in the Borderlands presents Nogales, a performance piece using theater, media, and masks to explore Jose Antonio’s 2012 death along the border, at Mesa Arts Center. Also in November, Performance in the Borderlands sponsors Lluvia Flamenca, featuring local and international artists including Angelina Ramirez, at Crescent Ballroom. ADVERTISING inRead invented by TeadsIt’s important to showcase Arizona as an incredible place of artistic production, Stephens says, adding, “So often, we hear of Arizona as a place things go to die.” DJ and music activist Lynnée Denise. ASU Performance in the BorderlandsIn January 2017, DJ Lynnée Denise will share a performative lecture rooted in her work on Afro-futurism, DJ essays, and theories of African diaspora. And in May, Performance in the Borderlands will close its 2016-17 season with Más, a docudrama written by California playwright Milta Ortis, whose Disengagedplay developed with Rising Youth Theatre premièred in Phoenix during 2014. Más was inspired by Tucson Unified School District'sban several years ago of ethnic studies classes. Despite its focus on border-related issues, Performance in the Borderlands has implications far beyond the U.S.-Mexico border, says Tamika Lamb, a longtime collaborator with the ASU initiative and lead partner for this year's bi-national artist residency. Performance in the Borderlands presses people to dialogue about things like gender, religion, and geography that too often separate and divide them, she says. “It helps people be open and look at the physical and invisible barriers in their lives, and talk about ways we can all come together,” Lamb says. Correction: This post has been updated from its original version to reflect that Lluvia Flamenca is sponsored by Performance in the Borderlands, not presented by PIB, and that Rashaad Thomas is not participating in Oasis. Please share a little of your story/background and the way your personal story connects to your artistic practice(s)? I am a second-generation Indian American, mostly-native to Arizona. I am a sister and a daughter. My parents moved to this country in the late 80’s, and their journeys, words or advice, and contradictions are some of my greatest sources of inspiration. I am a performance artist, with roots in dance. My training began with the classical Indian dance form, Bharatanatyam, which I still practice and teach. This particular art form is laden with cultural value and community, and without it, I would not be able to conceive of myself as am embodied storyteller. As I have grown older, my relationship to both the stories and myths contained in the movement vocabulary of Bharatanatyam, as well as my parents’ country of origin, has shifted in incredible ways. I have expanded within and outside of Bharatanatyam, to explore contemporary Western movement practices, as well as theatre, poetry, and comedy in my performance work. Greater performative depth has ultimately given me the strength and share my own stories, and challenge narratives handed down to me. What themes or topics do you address in your artistic and cultural work? Since starting to unearth and perform original work, I am most drawn to exploring the same concepts that attract me as an observer: paradox, borders, resilience, identity, and personal relationships. These are a few of the main sources that fuel my work, because in them I find room for myself and others. My work and my story, lives proudly and inherently in worlds of diaspora, bordered identities, and feminism – but amidst these tethers, I explore details of love, life, and curiosities. Humor, improvisation, and storytelling, are the threads with which I try to weave my pieces. Why is artistic expression important to political and social justice movements? Artistic expression, as a vehicle for social and political justice, gives us room to breathe and witness. The rules that govern much of social and political decision-making are intentionally shrouding. Artistic expression, on the other hand, makes explicit its intention to expose; to reveal; to make transparent. Artistic expression inherently does not have to fall within the constraints of politics, because the art gets to challenge and blur the assumptions politics, and even social justice, are built upon. And more simply, artistic expression is the ground for hope of being able to see and acknowledge each other’s shared humanity. All the ways that unity can feel inaccessible and idealized politically and socially, art manages to make possible once again. What is unique to Arizona aesthetics? Do you see a special arts movements happening here, if so, what does that look and feel like? In other words, why should people be paying attention to Arizona artists?

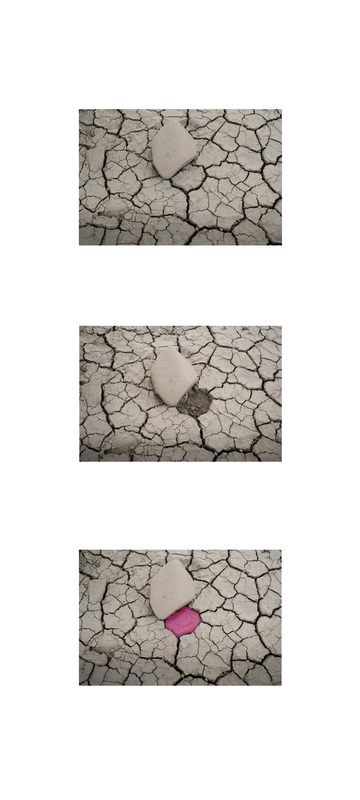

Just within the limits of my own artistic and social experiences in Arizona, I feel a part of an ecosystem of people shaped by their landscapes in sometimes imperceptible ways. The heat unveils a particularly kind of anger, while the expansive skies and powerful Saguaros fill us with a unique patience. The spread out and disconnected urban sprawl of Phoenix makes “stumbling upon” far less likely, and thus makes room for particularly hard, and intentional workers. Cities across Arizona that I am familiar with: Phoenix, Tucson, Douglas, Prescott, Chandler – all of them are attempting to make concrete their own identities, while being in communication with one another. In this sense, I believe Arizona artists and creatives have the potential for sharing resources and collaborating in incredible ways. Ways that cities with more engrained, and demanding identities and expectations have lost sight of. As if that isn’t rich enough, we live in one of the most politically and socially contentious states in the US: our border politics, insufficiently funded educational systems, and political climate at large are constant sources of inspiration; raw material, and offerings for engagement. What is on the horizon for you, and what would you most like to learn this next cycle in your practice? In March of 2016, myself and two of my greatest friends and collaborators – Allyson Yoder and Carly Bates – created intersectional, feminist, personal solo performances and presented them alongside each other. I am thrilled to be in conversation about restaging this work in the fall. I am also continuing to collaborate with ASU’s Performance in the Borderlands initiative and Grey Box Collective. As I continue to work with multiple creative containers, I am always curious about how to best challenge making visible my intentions, voice, and questions as a performer, while best respecting and honoring the intention of each container. In other words, how to best engage with questions that are inherently political, while challenging myself aesthetically, so as to best utilize art/performance as the medium for exploration. Can you share a little of your personal story and how it connects to your artistic practice and ethics? Who I am is indelibly tied to who raised me and the landscape that shaped my family’s story. I am a fourth generation Tucsonense with ties to this city from the early 1900’s. My family is full of hardworking laborers and mujeres con fuerza. As a child, I was constantly asking questions of everyone around me. Naturally, I felt the sciences were a right fit. But it wasn’t until I fumbled through my first degree in Animal Sciences at Cornell University that I realized I did not fit into laboratory culture. I found the scientific method a way for me to ask questions and come up with creative solutions to arrive at an answer, but I got lost in the tedium of the research world. It was at Cornell, in an alien landscape and foreign culture, that I began to question who I was and where I came from. I found an outlet for creative expression in film photography and I spent as much time in a photography lab as I did in the research lab. After receiving my B.S. in Animal Science, I took a few years off and decided to go back to pursue something creative. I ended up at the University of Arizona where I fell in love with the field of ‘visual communication’. When I started art school, I was afraid my overly analytical brain might not make anything worthwhile; “fine art” seemed so esoteric and disconnected from my reality. The field of illustration offered me a way into the world of art. The task of using creative visuals to illustrate information was like putting puzzle pieces into place. I was amazed at the power of art to transmit information: that an image could be both aesthetic and functional. The different mediums that I learned in art school became my tools to experiment and question the world around me. My ethics as an artist are grounded in my sense of place and my connection to the deserts of Tucson. As a kid, I was off alone in the Santa Cruz river throwing clods of dirt around. In art school, I continued to revisit these places of importance to me. My perspective as an artist starts from the dirt I stand on and I don’t feel that I can make work about things I do not have experience with. I believe as a visual communicator, it’s my duty to use my tools as an artist to explore ideas of social importance. My background in science really gives my work a different launching point and keeps my subject matter tied to the real world. What topics and/or themes do you address in your artistic work, and why? What mediums do you prefer to work in, and why? The desert, home, family, and social justice are consistent themes in my work. I don’t often start on a project unless there is a personal connection to me. I grew up in a large family with many grandparents, cousins, and aunts. I’ve been forever surrounded by that network of support. My identity is wrapped up in my rich heritage. I began to look at my family’s history within Tucson and I began to wonder, “What lives did my great grandparents live?” “What was it like for them to be immigrants?” “What was the Mexican American community like back then?” “Why does it still feel segregated now?” All of these questions informed my current project Abecedario del Sur and continue to inspire me to create more work. Another source of inspiration is the Sonoran Desert. I often think about my Great Grandmother who got to see the Santa Cruz running with water when she was a girl. The same river, now dry, that I would play in as a child. As far as medium goes, I will use whatever medium best pairs with the concept I am working with. I tend toward multi-step process-heavy artistic works. Sometimes I can get overly convoluted with process. One time, I had to design my own font in school so I started by shaping letters out of ground spices. I then blew the sculpted spices with a straw to spread out the letterform in an organic/distressed way. I did this same process with each letter of the alphabet, photographed, then transferred them to a digital program and created a font called ‘Tornado Type’. People have always been drawn to the letterforms of this project and when I explain the process, it’s like explaining how I did a magic trick. That moment is really satisfying for me as an artist. Why is artistic and creative expression important to social justice movements? Visual communication is such a profound way of telling a story. Social justice movements are so multi-faceted that as an outsider, it can be hard to understand the movement or connect with the ‘cause’. Artistic and creative expressions of social justice statements engage a wide audience by not only stimulating their eyes, but capturing their hearts! Another consideration is that the oppressed have often been left out of creating narratives about themselves. It is extremely powerful to put these tools into the hands of those who have much to say and much to reshape. I feel a responsibility as a Mexican-American with strong ties to Tucson, to engage with the people’s narrative and put this in opposition to what we are being told from white educators, law-makers and the media. Organizations like the National Association for Latino Arts and Culture are incredibly important in funding Latino artists, but also in creating a network of artists who support each other. I think it’s also important in a place like Tucson, where ‘Southwestern Art’ is so attractive to tourists, that artists of color from the Southwest use their art to confront stereotypes and reframe our experience in this land rather than relying on icons that further the mis-education. Can you share a little about your current project? My current project is titled Abecedario del Sur: a Geographical Alphabet Book (see above). The project began as an exploration of the typography found in the Southside of Tucson. I took photographs of the buildings and signs along South 6th Ave and South 12th Ave, pulling out a different letter of the alphabet from each sign. I arranged the alphabet geographically by laying out the letters by where I found them along the streets. Thus, the viewer is taken on a journey from North to South, emphasizing geography and place, thus the name: Abecedario del Sur (Alphabet of the South). The southside of Tucson is rife with stereotypes and has generally been considered ghetto and dangerous. My book aimed to shatter the conceptions and reveal the true beauty that’s always existed in my side of town. When I went out to photograph the signs for this project I was amazed at the diversity and richness of the hand painted signs that lined the streets. All I could think about was how I was being taught in school that great design comes from Europe and big cities, yet here in this humble, derelict side of town, I was surrounded by fantastic designs. After I graduated from the U of A I applied for and won the Artist Research and Development Grant from the Arizona Commission on the Arts in 2015. I used this funding to start interviewing the businesses owners whose building signs were featured in my book. I wanted to tell the story of the amazing people from my community who had built this landscape. I wanted to know who they were, how their businesses had survived, and what their experiences in Tucson had been. I come from a family of small business owners and I just wanted to know how, on this downtrodden side of town, so many have survived for over thirty years. I pulled in my sister Sharayah Jimenez, an architect and talented writer, to help me craft this narrative from our interviews. This year we have been going over the interviews I collected last year and started the writing process. Some themes that have emerged deal with the immigrant experience, resilience, hard work, and the importance of family. The book will be a mix of art, history, stories, and heart. In addition to this I’ve been screen printing select pages from my alphabet book to sell as stand alone pieces of art. I began working with screen printing because I wanted to create work that everyone could afford and that many people would want to engage with if they didn’t purchase the book. I’ve printed all the letters to spell ‘Tucson, Az’ and in June I was part of a group show in Phoenix that really opened doors and encouraged me to keep on going with this artist’s life I’ve created for myself. What is unique or powerful about the arts movement in Arizona at this time? What unique aesthetic innovations do you see happening here? I’ve only been a working artist for 2 years, so I have more connections within the social justice community in Tucson than the artist community. I’m always amazed and inspired by the activists here. I know many people who have moved to Tucson to be a part of the social justice community and contribute to the work here. And likewise, alot of talented creatives have flocked to Tucson to take advantage of the affordable living and be a part of our active art scene. I find it interesting that the two scenes don’t often overlap and in fact they seem like completely disparate communities. Perhaps this is due to the fact that so many of the artists in town are transplants, maybe it has to do with subject matter. What I do know, is that the Tucson art scene is relatively unpretentious and there are many places to show your work and opportunities to collaborate. I think the slow relaxed vibe of Tucson really encourages us artists to take our time with our work. I see a commitment to traditional art forms like muralism, graffiti, painting, and print-making. It’s refreshing for me to see less digitally reliant artists working in Tucson. I just hope that in the future more artists are willing to engage with the activists in town and visa versa.

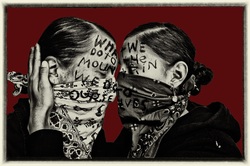

Can you share a little of your personal story and how it connects to creative/cultural/artistic work? When I was six years old I would put a towel on my head and dance to Gloria Trevi’s “Pelo Suelto.” I felt free and I felt powerful. I migrated to the United States when I was 8 years old. In 2006, I started organizing against Arizona's Proposition 300, which ended my college education as an undocumented student. I came out of the closet and as I moved in queer spaces. I was struck by the power that drag queens hold over their audience. Theater has always been part of my life, and I decided to take on drag performance to organize in a way that was relevant to all of my identities and communities. Once I have the mic, I can say whatever I want. I can talk about themes that are uncomfortable or ignored. Drag is an art form that lets my face be my canvass and my body create my message. When we hold Queer ARTivismo events, we open up space for others to take on this challenge in their own unique ways, to find that place of expression where identity and justice meet. Note: Proposition 300 is a referendum approved by Arizona voters in November 2006. Proposition 300 provides that university students who are not U.S. citizens or permanent residents, or who do not have lawful immigration status, are not eligible for in-state tuition status or financial aid that is funded or subsidized by state monies. What is Trans Queer Pueblo, and what is on the horizon for your work? Trans Queer Pueblo is an LGBTQ+ migrant community organization. We work to create cycles of mutual support and cultivate leadership to generate community power toward social justice. We are just incorporating this year, after 5 years of work and we will be cementing our work toward migrant family acceptance, economic justice, access to health for LGBTQ+ migrant community and community defense against criminalization. We are excited to be working toward a home for our QTPOC family here in Phoenix, which means that we’re launching a fundraising campaign and planning gardens.  What themes or topics do you address in your artistic and cultural work? The work of Trans Queer Pueblo is focused on building the power of LGBTQ+Migrant and PoC communities toward social justice. Within TQPueblo we work on Health Justice, Family Acceptance, Community Defense and Economic Justice. To keep all of this heavy work going, it is essential to have creative space to nurture those doing the work and to welcome in the broader community around them. We find that our political work has to have a cultural home and our contribution to that is our Queer ARTivismo space. At the ARTivismo events there are few rules: community members are invited to show off or try out different art forms. We create a fun and relaxed space that is centered on queer and trans people of color where they can address the joy, sorrow, hope and anger in their lives as they see fit. Why is artistic and creative expression important to social justice organizing and movements? Our movement is a product of our culture and a tool to work on our culture is art. If we use art to create a culture that is independent, rooted, and liberated, that culture will bring more people and perspectives to the movement and nurture those people as they do the work of building social justice. Our culture must provide a home in which our resistance can live. Creative expression allows people to engage in a different way. It allows the public to connect with what is going on in a more personal way. Art and creative expression allow us to learn across experiences and are an important tool to bring communities together. What is special or uniquely powerful about Arizona artists and aesthetics? Arizona aesthetics and artists are uniquely powerful because they are driven by day-to-day experiences in "ground zero" of anti-LGBTQ+ and Migrant realities. The aesthetics and perspectives that come out of Arizona challenge the norms and push the boundaries.  Cynthia Franco (Tijuana - DF) es poeta, performer, cuenta cuentos y gestora. Trabaja como subdirectora y Coordinadora de talleres del Centro Transdisciplinario Poesía y Trayecto, A.C. Kate Saunders (Phoenix - DF) es performancera y directora del proyecto Dos Verdades. Cuéntenos sobre su proyecto Donde Dos Verdades Se Encuentran. Cynthia: Dos Verdades es un proyecto que trata los temas de seguridad y hogar entre México y Estados Unidos a través de siete escenas performáticas donde se reflejan cuestiones de violencia, industrialización, explotación en maquilas, prostitución y conflictos como la discriminación que se acciona a partir del lenguaje. Al final, intentamos resumir todo lo anterior con metáforas concretas. Kate: Dos Verdades es un dialogo a través de escenas performáticas en las que podemos explorar temas de hyper-seguridad, miedo del otro, explotación e identidad. ¿Qué significa para ustedes que el proyecto sea binacional y bilingüe? Cynthia: Para mí significa multiculturalidad, aceptación entre dos espacios en conflicto y sobre todo, atravesar nuestras propias fronteras y expandirlas. Significa abrir puertas, deconstruir muros desde lo micro a lo macro. Kate: Para mi significa nuevas posibilidades de relaciones y entendimiento, no sólo entre nosotros como nuevo equipo, pero cruzando culturas y naciones. Significa que realmente existimos en un estado de traducción perpetua y que estos temas no sólo son de un lado, pero que es una conversación que nos conecta. No siempre es fácil, pero con esta dedicación y compromiso al trabajo, nos ayuda escucharnos uno al otro, abrirnos a ideas diferentes e intentar comunicarnos mejor y escuchar más. ¿Cómo se relacionan con el proyecto personalmente? Cynthia: Principalmente, con la resolución de casos particulares dentro del contexto donde nací. Que es Tijuana. Un espacio por demás cargado de sacrificio y dolor. A partir de esto, Dos Verdades me brinda sanación y encuentros con experiencias particulares. Mi intención es provocar diálogos en torno a la performatividad del tema en escena. Kate: Yo en el sentido de que soy de los Borderlands de Phoenix, Arizona, a unas tres horas de la frontera y de un estado conocido por su racismo y su política extrema, pero al mismo tiempo soy blanca y de clase media, entonces realmente la frontera no presenta repercusiones inmediatas para mí. Me urge investigar como funciona este privilegio, identidad y herencia en conexión con estos temas relevantes. ¿Qué podemos esperar de Dos Verdades en el 2016? Cynthia: Alcance internacional a partir de presentaciones en diversos puntos y espacios alternativos. Dentro del público asistente, una transformación sobre sus esquemas y estereotipos sobre “las zonas border line”. Sobre el equipo, espero unificarnos y que la obra tuviese este sentido de migrar e ir desarrollando la obra conforma nos afecta a nosotros. Kate: Estamos continuando con el proceso de creación y ensayos con planes para presentar el proyecto nuevamente en el DF: en Teatro Lúcido en junio, y luego en otros estados de México durante el año. Esperamos poder hacer un tour de la zona fronteriza más adelante en lugares como Tucson, Phoenix, Nogales y Tijuana. ¿Qué les gustaría que fuera el impacto social de este proyecto? Cynthia: Me emocionaría que se replicara en otros puntos internacionales y sobre todo, que los asistentes tuvieran conclusiones que le detonen procesos creativos y evolución desde dentro hacia afuera. Es decir, desde si mism@ hasta las conductas con su otredad y contexto. Kate: Nos gustaría que se abriera una conversación con las audiencias de los dos lados de la frontera en la que puedan ver hacia dentro y preguntarse cómo estoy implicado en esta situación? y subrayar la lógica de estos temas en su poder de justificar la opresión que está presente en los dos países y desde uno hacia al otro. Can you share a your personal story and how it connects to your artistic work? I am a native Phoenician - and my mother also was a native of this area, born in Tempe, Arizona. My upbringing was submerged in white privilege with little awareness of the indigenous people surrounding me in my home state. Although my household was liberal in its thinking, it would not be until the jolt of 09/11 when my intuition about the status quo would be fully awakened. I had been practicing as a graphic designer for nearly 35 years, when I was inspired to return to ASU to explore further education. As a result of a semester’s study of Apartheid and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s work after Nelson Mandela’s rise to power, I found myself in South Africa for two summers. Restless after these intense, and life-changing experiences in South Africa, I was drawn to seriously develop an artistic practice as a means to respond and voice my frustrations with US policies in the global neighborhood. The material basis of my work employs fiber-based techniques, which, given my 1950’s white female upbringing, offers a unique conceptual underpinning. I seek to exploit the soft connotations of these traditional house-making “crafts” to convey hard truths of the social issues of our time. Further, my professional practice as a graphic designer emerges to combine aspects of typographical messaging and digital imagery with the natural mechanics of textile structures. What themes or topics do you address in your artistic and cultural work? Thru the filter of my own experience as a white female born in1950's America, I explore themes of assumed entitlements, homogenization, marginalization, and human obsolescence - social divides we’ve come to accept as normal cultural paradigms. In questioning this acceptance, I recognize the insignificant - marginalized found objects and disenfranchised people. Driven by a desire to make right, the work I do reflects my own handwork, but also orchestrates handwork of people experiencing homelessness or interested community members through public interventions that seek to socially engage the hands of many to create a larger whole. My work exploits traditional fiber techniques as conceptual tools for aesthetic, social communication to examine a society of which we are all a part - as bystanders, participants, victims and perpetrators. Why is artistic and creative expression important to social justice organizing and movements? Humans are drawn to “the spectacle”. The artistic spectacle - whether visual, audible, or performance - offers the opportunity to upset the norm, to expose new or previously hidden perspectives on social issues through meaningful, and often visceral experiences. Artists work within (or without) parameters of their own making, and have the power to awaken empathy and connect common lives to large ideas through commonalities we all possess. It is through these non-tangible connections that hearts and minds are affected, changed and activated to live with more careful intention. What new directions can we expect to see in your work and what is on the horizon for you? At this point in time, having just come off of a few large efforts to make tangible work, the focus of my practice is in the absorption of new information in order to develop meaningful ways to deliver teaching experiences to a various of student types. In addition to my teaching practice on the ASU campus and at Paradise Community College, I was selected as one of eight cohorts to participate in the inaugural Creative Aging Institute organized by the Arizona Commission on the Arts. The aging population is an important group that is often marginalized and “warehoused” in our society so focused on youth culture. I’m interested in exploring ways to connect and invigorate aging participants through meaningful artistic experiences. In addition, I have been selected as one of two artists by the City of Phoenix Office of Arts and Culture for a residency at the 27th Avenue Waste Treatment Facility. We have free reign to create work from our experiences and through the materials available at this facility. I am hoping to combine object making with exposing the cycle of our waste - with a focus on the people whose job it is to deal with the cast-offs of our daily lives. This will be an exciting opportunity to learn and create the work that will emerge from this residency. What is special or uniquely powerful about Arizona artists and aesthetics?

Arizona is a border state with Mexico, and in the crosshairs of one of the most contentious political issues of this election season - immigration reform. Maricopa County is strapped with one of the most vocal and abusive perpetrators upon the incarcerated population, - Sherriff Joe Arpaio - his department under federal investigation for the practice of racial profiling and abuse of undocumented people. Our state legislature has a history of racial inequities in its voting record, passing SB 1070, and refusing to recognize the MLK holiday until the economic impacts of this decision came to bear - to name only a few. In addition, there are over 20 different native tribes on Arizona soil, with over 1/4 of the state designated as reservation land. Arizona has the second largest Native American population of any state in the US. Yes, Arizona itself is a political spectacle - fertile ground for the artistic spectacle. In addition to the political rhetoric, traditional imagery and artistic practices of indigenous peoples offer a legacy of artistic expression borne of Arizona - with its particular flora, fauna and mythologies. There are so many brilliant artistic voices working in Arizona, with a story to tell, experience to enlighten, awareness to incite. In making artistic work that speaks to their particular experience, Arizona artists have the opportunity and power to craft messages that are meaningful in the broader context of social justice discourse.

Photo credit: David Emitt Adams

Can you share your personal story and how it connects to your art practice?

I’ve lived most of my life on a divided line, living in a linear world with a nonlinear mind. I’ve always wanted to communicate using my own personal format. This has lead to a lifetime of developing that format and is always a work in progress. The need to touch and build with my hands has always been a part of my life and, with that, I feel very privileged. Often, my family moved to new towns and cities. This was an accepted part of my life that helped me keep a fresh perspective. I believe this, and my Indigenous roots, have been a major contribution to my art practice. What are the themes of your artwork, and why do you choose them? As a contemporary artist who practices largely in Indigenous issues, I often trace my concepts through the western projected narrative as well as a rooted personal Indigenous dialog. Historic western imagery and ideals act as stains that hammer through most of my work and position themselves into boldly-laced discussions. Imprinting an expired label onto archaic capitalistic driven social constructs tends to be my main target. I continually find a need to make a call for Indigenous-minded social, political, and environmental progression within our society. The lack of it has buried us and left us with a disconnected reasoning with ourselves.

What does it mean to you to be an artist living and working in Arizona today?

Arizona is a wonderful place. It is Indigenous land that still responds to the people that belong to it. It also has a bit of a bite to it that stirs the dust and strikes discomfort into the eye of humanity. These are the things that keep me, as an artist, alive and attentive. I appreciate what it has given me and I’m always working diligently to give it justice. What projects are you working on now? What can we expect to see from you in 2016? I’ve been pretty busy at the turn of the year moving my print shop, WarBird Press, into a more public space. With this accomplished, one project that I’ve been fixated on has been my letterpress work that I’m using for public engagement. I have an old vending machine that was used on the streets to sell newspapers and I’ve been exploring the levels of public interaction with it. The history of prints, prints as media and as propaganda, are deep within the documentation of our internal framework as a society. I’m revisiting that narrative by applying adjusted prints to the existing archives. Random and some not-so-random places in the public are scouted as drop spots for the vending machine. The prints are then placed inside for the public to purchase at a price well below market value. Newspaper vending machines have quickly been driven to the shadows of society by digital media and, with that, the main use of the print as a multiple has been lost. I use digital media as the conductor that directs traffic to the specific location of its predecessor. It’s a play to recall our conditioned notions that frame the selected notes of history.

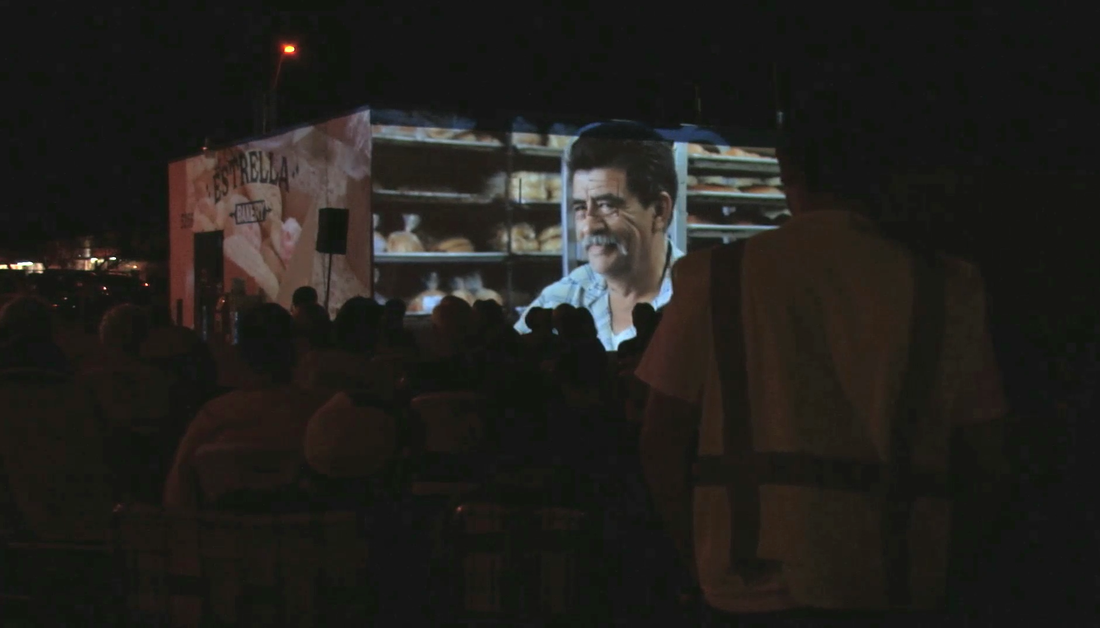

Through original videography, community events, street art and urban site-specific projections, Barrio Dulce celebrates pan dulce and the Mexican bakeries that support neighborhoods, community and culture. Pan dulce is hand-crafted artisanal bread made by proud bakers, and consumed daily by many people in the Tucson, Arizona and Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua where the Barrio Dulce project has been produced and presented. During the project, artists Gabriela Duran and Heather Gray worked with La Estrella Bakery (http://laestrellabakeryincaz.com/) in Tucson and Panadería Aurora in Juárez and recorded interviews and video of the baking process, gathering stories from the owners and workers, gathering stories from the owners and workers. Barrio Dulce hosted screening events at the bakeries or nearby, rather than screening the videos to an outside audience at a theater or film festival. At the events, the videos are remixed and projected large-scale on the buildings. The images and sounds light up the neighborhoods, and the bakeries publically perform their stories, which are normally hidden behind walls. Neighbors gather in the streets or parking lots, eating pan dulce, and watching the projections animate a space they might visit everyday.

How does this project exist bi-nationally? Tucson and Juarez are cities with strong traditions of pan dulce. They are of similar size and latitude with distinct “border identities”, and social and political issues that are tied to border dynamics. The project has also been presented live in Guadalajara, and exhibited in Valparaiso, Chile --cities with their own incredible traditions of bread and baking. The project was created by Gabriela Durán, a new media artist and professor at the Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez, in collaboration with Tucson-based artist and videographer Heather Gray. Gabriela is connected directly and emotionally to the project because of memories of growing up in her father’s bakery in her neighborhood in Juárez. About halfway through the project Jellyfish Colectivo (http://jellyfishcolectivo.com), a street art collective in Juárez, joined us and created a mural celebrating negocios del barrio leaving a more permanent mark in the neighborhoods. What does it mean to be artists living and working in Arizona today? It is an enormous privilege and responsibility to live in a desert and a border region. A lifetime of questioning and learning is required to try to understand how to live in a place that is both fragile and resilient with a complex history of migration, and colonization. Heather has lived in Arizona her whole life. Gabriela has lived in Juárez her whole life. They are committed to staying, inspired by the way artists and communities respond to the political climate, assert themselves and their stories, survive, and seek justice and social change.

What can we expect to see from Barrio Dulce in 2016?

We are focusing on bringing Jellyfish Colectivo for their first street art engagement in Tucson, to continue the cross-border exchange and conversation. There is still a lot of information we have the needs to be presented. For example, when we were doing interviews in Juárez, we learned that bakers used to have a union that helped create fair paid jobs for bakers. We also found unique stories about each bakery. For instance, there was one bakery in Juárez that, in its golden years, would be open 24 hours. People would go at 4am to get a sweet bread and free coffee. We would like to present this part of the project either online at barriodulce.com or at a conference. How do you feel that Barrio Dulce creates or supports social change? Today, many Mexican bakeries and other small businesses on both sides of the border are disappearing, downsizing or automating their process under pressure from supermarkets, low-wage jobs, downturned economies, urban revitalization schemes, marginalization of migrants and violence. As a result, decades of memories, skills, meaningful well-paid jobs, and culture with connections to place are at risk. The two cities face different threats, though it is the same source --the globalization of corporate neoliberalism-- which has different consequences on each side of the border. Barrio Dulce poses the idea that something as humble as a bakery holds a margin against these threats. The projections at the bakeries help rethink a relationship to the city and neighborhood itself. Our project reflects upon the importance of Mexican bakeries, not only in terms of community but also seeing how they form and affect our identities, activate the local economy, and create safer environments. Without overstating the impact of one art project, we see the need for creative responses to our situation, because we know art has the power to shape the collective imagination over time. DulceTucson from Heather Gray on Vimeo. Photo Credit: Fronteras Desk  What is your personal story and how do you connect it to your arts practice? I was born and raised in North Carolina. Although I was a child during the turbulent period of the 1960s, I witnessed a lot. I remember seeing signs over water fountains indicating “white only” or “colored only.” I remember black-only movie theaters and swimming pools because we weren’t allowed to go to the white swimming pool or white theaters. My father’s mother lived in Wilmington, NC. As a kid we’d travel to visit her from my home in Raleigh several times a year. Because we traveled through the heart of Klan country my parents would have me pee into an empty soft drink bottle, afraid of stopping at white-owned gas stations. Yet, in the midst of this craziness, I went to an alternative Quaker boarding school when I was 12, where I was one of 3 black kids out of a student body of 24. I was in this culturally rich, integrated, loving environment for 3 years which were the formative years of my life from ages 12–15. My first experience in a darkroom occurred at the Quaker school. My exposure to a life of service and living simply with consistency between one’s politics, spiritual practice and one’s work happened at the Quaker school. Ironically, the examples of the worst of humanity and the best of humanity were found in the same state. Both the experiences of hardcore racism and loving pacifism with a strong sense of community influence the work I do now and my art practice, which I identify as a celebration of the dispossessed. What themes are present in your art? I come from a tradition of humanistic, documentary photography. Traditionally, this photography is black and white and focuses on the process of getting to know people over an extended period of time and attempting to tell their story and reveal their truths through photo essays. I just did a retrospective show in December and the themes were primarily those of love, compassion and empathy –moments from everyday life that have a universal quality. Can you tell us about the medium in which you create? I spent 22 years shooting black and white film, which I developed in my home darkroom. Though this resulted in several gallery shows, the people I photographed weren’t seeing the work. I’ve always been drawn to street art since it first blew up in the early 80s. I spent 3 months in Brazil in 2009. During this period I spent time with artists creating art on the street. The artists in Brazil showed me work by the French artist JR, who enlarges black-and-white photographs to cover the facades of four-story buildings. This was my first time seeing how a photograph could be used as a street art medium. Upon returning to the Navajo Nation, I began to experiment with my old negatives and started placing them along the roadside on the reservation. I learned early on from roadside vendors that they appreciate having art on their roadside stands as it encourages more tourists to stop. Also, in a community with a high rate of unemployment, high rates of teen suicide and drug and alcohol abuse, I wanted to use imagery along the roadside that reflected back to the community some of the values of love and cultural heritage I’d captured during my time on the Navajo nation. Since 2009 I’ve been using large-format, wheat-pasted, black-and-white photographs adhered to roadside structures as my primary medium. What is JustSeeds and why are collectives important? Justseeds is a cooperative of 30 socially-engaged artists and activists scattered across north America whose work addresses themes of social justice, environmental justice, gender quality, prison reform, veteran advocacy and so on. It was an honor for me a year ago to get invited to join this group of like-minded folks advocating for the collective good. To live and work in relative obscurity on the Navajo Nation, it's important to feel connected to a larger community where ideas are shared and critically evaluated. I also appreciate opportunities for collaborating. You asked why are collectives important. A book of activist art was published recently titled "When We Fight, We Win." I'd alter that by saying when we fight together, we win. Do you think that Arizona has a unique aesthetic voice? No doubt. There are the cliché images of Arizona art of coyotes wearing bandanas howling at the moon or Kokopelli, but then there's the more socially-engaged art that speaks to immigration issues such as SB 1070, illegal deportation, protection of sites sacred to local indigenous tribes, water use and coal and uranium mining. Arizona is in a unique position to serve as a model for the remainder of the country with legislation regarding protection of sacred sites, immigration reform and gun law reform after the tragic shooting Tucson in 2011; however, politics and mindsets being what they are here, it provides an ongoing opportunity for activist artists to keep fighting to shed light and spread love. As Martin Luther King, Jr. said, "the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends towards justice."  Can you share your personal story and how it connects to your art practice? I grew up on the US/Mexico border and have lived on both sides of the fence: in Douglas, Arizona and Agua Prieta, Sonora. My family and I have lived primarily in Douglas. We lived in Agua Prieta during my middle school years and I always remember how often we would cross back and forth, sometimes 2 to 3 times a day. We were "regulars" at the port, my mom’s name and car were known by the majority of the custom agents, and we definitely had our favorite agents whom we hoped would "check" us. Rather than the questioning being about why we were crossing or what we were bringing back, the interaction was more about how our weekend was, or how the agent’s parents were doing and vice versa. At the age of twelve the experience of living the border daily was not only mundane and routine, but it involved friendly interactions and relationships with federal agents. For my brother and me, it was a game of whose turn it was to pick the lane and guess which agents would be waiting for us. Fast-forward to 2005, which is the year I moved to Phoenix to pursue a degree and career in art: I found out quickly that my experience of the border was incredibly different from the perception of the people around me. My art practice became rooted in my quest not only to change that often negative perception, but to expose it. What are the themes of your artwork, and why do you choose them? The themes of my work range from feminist perspectives, life as a border citizen and, at times, a combination of the two. These themes chose me because they define me as a female who has grown up atop a geopolitical boundary too often used as political fodder and not regarded enough for its fertile, rich and vibrant culture, people and scenery. As an artist, I can have a voice in the public sphere that makes visual what the border means to me. What I love about making art about the border is that it's not only about Douglas and Agua Prieta, but it can mean something to folks living on another border somewhere else in the world. I hope the meaning can transcend geography, cultures and ideologies. Do you think there is a unique aesthetic and artistic movement in Arizona? Yes, I think there is a movement in Arizona. To me, the movement is about the simple fact that we're all the same, fence or no fence. Whether you are from that side or this side, it shouldn't matter, and it shouldn't give us the right to act unjustly to one another. The aesthetic movement has recently been about the border fence, which speaks volumes for a community like Douglas, as we're in the process of redefining who we are as a city and globally-relevant place. If you consider the recent work of Postcommodity, Ana Teresa Fernandez, Gretchen Baer and Aspir JHF, all of them used the physical fence as material to create art. The themes of these works are about remembering and imagining a time when the fence was non-existent, and the way in which we are connected not only through blood, but also through symbols and systems like capitalism. Artists want the world to know we are the same on both sides of the fence. In many cases we are literally family, and many people are disregarding history and where they came from at a time when we are bombarded by negative rhetoric surrounding our community. I feel artists are stepping up to represent this sentiment, which not only holds regard for the battles we're as facing as a border community, but also the battle that indigenous people and minorities are facing in the U.S. and abroad. What projects are you working on now? What can we expect to see from you in 2016? The Mexican Woman's Post Apocalyptic Survival Guide in the Southwest: Food, Clothing, Shelter, y La Migra is the newest project I am working on, which is a multiphase piece that consists of large-format photographs of 12 women who live in Agua Prieta, Sonora, and who are part of the non-profit organization DouglaPrieta. These women are experts on living sustainable lifestyles: they run a communal garden, raise livestock, make clothing, produce bricks for building --all while living on the outskirts of a highly-militarized border. The second phase of the project will be a how-to book co-produced by the participating women. This project is supported in part by an Artist Research and Development Grant from the Arizona Commission on the Arts. How do you feel that art can create or support social change? Art supports social change. Actually, it creates social change. That's something I think many artists imagine. That's what keeps us doing what we do. At the end of the day, if our art sparks an out-of-the-norm conversation or inspires a new perspective, I think that's great in and of itself. In my opinion, as artists in this technological generation that is hyper-connected, so many of us feel responsible to change the world. I believe in the power of numbers and consistency: if you have a message, find 100 ways to say it, and then invite someone else to say it with you. Can you share your personal story and how it connects to your art practice? It’s hard for me to separate my personal story from my arts practice. Growing up in rural Arizona near the US-Mexico border, art was first a tool for escape, a tool for imagining an experience larger than my immediate surroundings. What I didn’t fully appreciate at the time was how much that landscape would continue to manifest itself in my work: the huge sky, the rolling grasslands, the continual thirst for rain. Also the linguistic and cultural landscapes, the physical reality of the border as a dividing line, the edge of the world–– that’s how it was first presented to me. Later, after living for most of my 20’s in central Mexico, I came to understand my experience as that of a fronterizo–– though my blood is Irish-Slavic, my cultural experience is inseparable from the border. My poems are written in Spanglish because that is my most comfortable linguistic mode. To be bilingual is to be a bridge. To have privilege is to have the responsibility to spread it and subvert it. An awareness and engagement with social justice is a necessity. I’m always moving between worlds and arts media. What are the themes of your artwork, and why do you choose them? I find that others are better at articulating themes in my work than I am. That said, for me it’s the land. And how cultures interact with it. I am of a place that is staggeringly beautiful, and laced with deep injustice. Do you think there is a unique aesthetic and artistic movement in Arizona? Claro, though it’s hard to put my finger on it. I know that the last five years have been especially tough here: SB1070, Ethnic Studies ban, austerity, abysmal education funding, increased militarization, public officials running on fear. Thing is, it’s a lot bigger than the last few years, all this stuff has roots that go way way back–– at least to statehood, to colonialization and indigenous genocide. All that said, to associate the word Arizona only with backward politics is just lazy. Look beyond the headlines, spend time here, attend events, break bread with community. What’s beautiful is the way artists and communities have responded to the oppression, both directly and indirectly. The arts movement is Arizona is socially engaged and community-based because here there is no other way. There’s something about how the artists work together here, something about the land too. The desert is simultaneously a muse and a killer.  What projects are you working on now? What can we expect to see from you in 2016? My practice took a big turn in 2015 after the publication of Sonoran Strange. I unexpectedly had the opportunity to buy a house in Tucson, and for the first time I have a small piece of land for which I am responsible. Lately I’ve been spending my time swinging the pick and shoveling earth, quite literally doing groundwork. I’m building a rain-fed urban desert oasis that will partly feed my family and community. I’m interested in the intersections of permaculture, venue design, community, performance and relationship to place. Only recently have I begun to realize that this work isn’t taking away from my ‘art time,’ rather this is my art in this time. This is also arts practice. I hope to apply what I learn on this project to other, larger and more public spaces. Which leads me to think about La Pilita, the small venue in Tucson’s Barrio Viejo that I’m now co-managing with the social justice & spoken word organization Spoken Futures. Art has such a beautiful way to bring people together, in 2016 we’re looking to begin using this small space to affect long-term impacts on Tucson’s cultural landscape. Adam Cooper-Terán and I continue to collaborate as Verbo•bala Spoken Video, and this year we’re scheduled to work with Borderlands Theater and others to create a new series of performance vignettes in the style of the Sonoran Strange performance. We’re going to be looking at specific sites in the Tucson basin that are tied to local identity and culture. I’ll also continue working with young people at a local alternative school, with Spoken Futures, and while traveling. I’ve been working professionally as a DJ for many years now, and this year I’ll continue to play 1-2 days a week, Friday nights at Hotel Congress and beyond. Hopefully amongst all of that will be the time when poems come. In what ways does performance impact social change? In other words: Why performance? My colleagues Faviana Rodriguez and Jeff Chang of CultureStrike are fond of saying that you change the culture first, then the politics will follow. I can’t think of a more succinct way to put it. If we’re going to survive as a species and maintain our humanity, we’re going to need to stretch our imaginations in new directions and depths. Performance for me is the laboratory, a space of free imagination, where the body opens its vocabulary and arts media mix–– in performance we expand what’s possible, what stories are told, how, and by whom. Performances weave themselves into the consciousness of an audience, and from there to wider society. And that’s just the beginning of what performance does. You can find more information about Logan Phillips' work: www.sonoranstrange.com Border/Arte's mission is to explore the relationship between art and politics. We asked each of our collective members to share the ways their artistic and/or cultural work grapples with social issues. This week we talked to Kate Saunders, now living in Mexico City, about these issues.  What are the themes of your artistic practices and why? The principle themes in my artistic practices are feminine identity, queer identity, home, border politics, and the desert. To me they are all connected and I especially find rich metaphor in the desert for almost every aspect of my storytelling. These themes are what I graze against or smash into in my everyday life. They are the politics that build my body and the walls around me, so I find that by unearthing them through creative work and cultural partnership we are able to learn (or unlearn) more deeply and fully about important aspects of our lives. I find that by moving through these themes we are more able to connect to memory and through sharing these stories we are able move ideas into models that better serve us. What is the role of art in shifting political awareness and creating a more equitable society? I believe that the role of art is to seek new ways of understanding; to share infinite histories, memory and perspectives; and to provide space for reflection and discussion, which I believe are all necessary actions for shifting ideas, political awareness, and fostering a more equitable society. How do you understand your work in the context of Border/Arte’s core values and mission? I am from Arizona and currently working away from home, [the distance] has made it more important for me to understand where I come from and how that is represented in my work. What are the stories we are telling about home? What does it mean to be from the borderlands? What politics have we inherited and what are the politics we embody? These are some of the questions I am exploring in my work and artistic/cultural partnerships. As part of Border/Arte's Living Room Sessions series, we ask artists to share their thoughts on a broad range of personal and political topics. We asked Ana Teresa Fernández to share her feelings about home and vulnerability, and her thoughts on politics and art.

As a Mexican-born national living in the US, can you share how you move through these worlds. What is home for you? What are those places where you feel most vulnerable and open? Home is a space I am still trying to decipher. I feel most at home when I'm submerged in a conversation in Spanish in Mexico that has a level of wittiness and banter that is not translatable. I feel most at home when I'm free to roam in my activities in San Francisco and not have to explain or justify anything to anyone, moving from the water to my studio with ease. I feel most at home in the embrace of my mom and dad when I visit them in San Diego, CA. I feel most at home when I arrive to my small surf shack in San Francisco and can sit in my tiny kitchen and write, getting lost in some of the most absurd ideas, allowing myself to dream without any borders. These are the places where I feel at home, in conversations; expressing language, moving my body, provoking my mind. Home is not just one concrete place, but a series of moments that make up a notion of home. In these, I feel I can most be myself and reveal parts of me. What are the main themes of your artistic work and how do you approach them? The theme that most interests me is the relationship between Seen/Unseen. This becomes an umbrella for engagement in politics through immigration, gender divide, identity struggle. What usually gets me intrigued is when I come across information for the first time of an injustice that has been around for sometime, and I ask myself, "why hadn't I heard about this before? How long and why is it going on? And what can I do to change that or amplify the awareness of it?" Can you share your thoughts on the importance of art to make social and cultural change? This first step for me is to create an awareness. This I attempt to do not just with stats and figures, but by presenting the same problem in a new or different light, trying to engage or re-introduce an old conflict in a new way that is more approachable or engaging. This usually begins a conversation. Once you have a conversation and catch people's interest, this is when you mobilize change or action. People do not often realize that they themselves have agency to change what is around them. Often times there is the belief that change comes in monumental forms, but in reality, sometimes it is just the smallest of actions or involvement that can really "stir it up," as Mr. Marley says. You recently came to Arizona for a 10-day statewide residency, which garnered international attention. Can you talk about Arizona as a site for artistic and cultural work? What is unique and special about this state? That was my first time in Arizona. And what a place! Immense natural beauty, expansiveness... Yet at the same time there is a spectrum of extremes in people's cultural beliefs and approaches. Very liberal and open minded folks in the same pool as extreme right wing conservatives. It makes for very tricky waters. You get people with the willingness to create change, but you are met with harsh resistance. I feel California is much more like Switzerland, more laissez-faire, not much stirring, but not much opposition. I received a lot of love, but also a lot of hate in Arizona. There is a perception that working artists are secure and sure of their place. Can you share some aspects of yourself and work that feel insecure and are still growing? In other words, those aspects that need constant courage and daring to show themselves? This is the million dollar question. The notion of security is completely false. One thing I do know is that the landscape of the artist life is constantly in quick sand, and that is largely attributed to the lack of infrastructure placed in our culture to the arts in general. No Ministry of Culture exists! I always thought Quincy Jones would make an epic Minister of Culture. Or Minister of Cool. But in all seriousness, artists exist where often times there is no constant paycheck. This creates a bit of an Odysseus position, where you have to become ingenious and cunning as to how you move in the world , learning all sorts of societal languages to contort into something that will keep you afloat. This, coupled with the idea that we exist in a state of constant awareness and openness to take in the troubles of the world and create work that will speak about it in an expansive, and interesting way.... I mean it is like we are the sponge & the punching bag. But having said all this, it is a privileged position, because so many people never get asked for their opinion, so many people expand on notions of the "whys" of the world, we exist in a constant state of questioning and receptivity of thought and action, and this is a privileged position, to create a voice to create change, is one of the most unique and special places to be in. And for one to be able to do that, one must feel secure in their voice, in what they believe in, and that is sacred. How would you most like to grow artistically and personally this next year? Being more open, allowing myself to be more vulnerable and willing to change and adapt. Not to become someone else, for others, but to become more expansive with my practice of awareness and empathy with others. As part of Border/Arte's Living Room Series we ask artists to share their insights on a broad range of personal and politics themes. We asked actress and producer Anu Yadav to share her thoughts on the unique power of performance to move social change, and to share some of her personal story as it informs her community organizing through performance. What are the themes present in your work?